EDUCATION MATERIAL

BARRETT'S ESOPHAGUS

National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

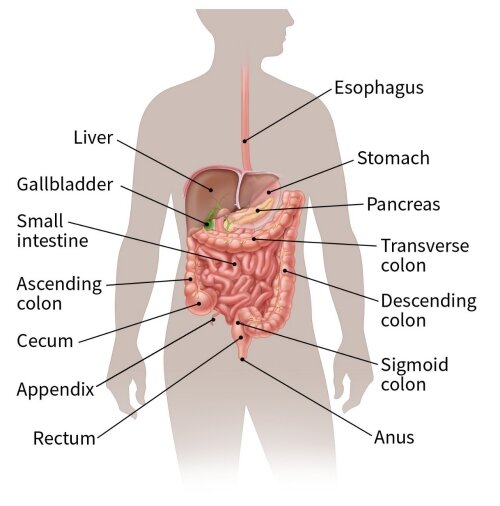

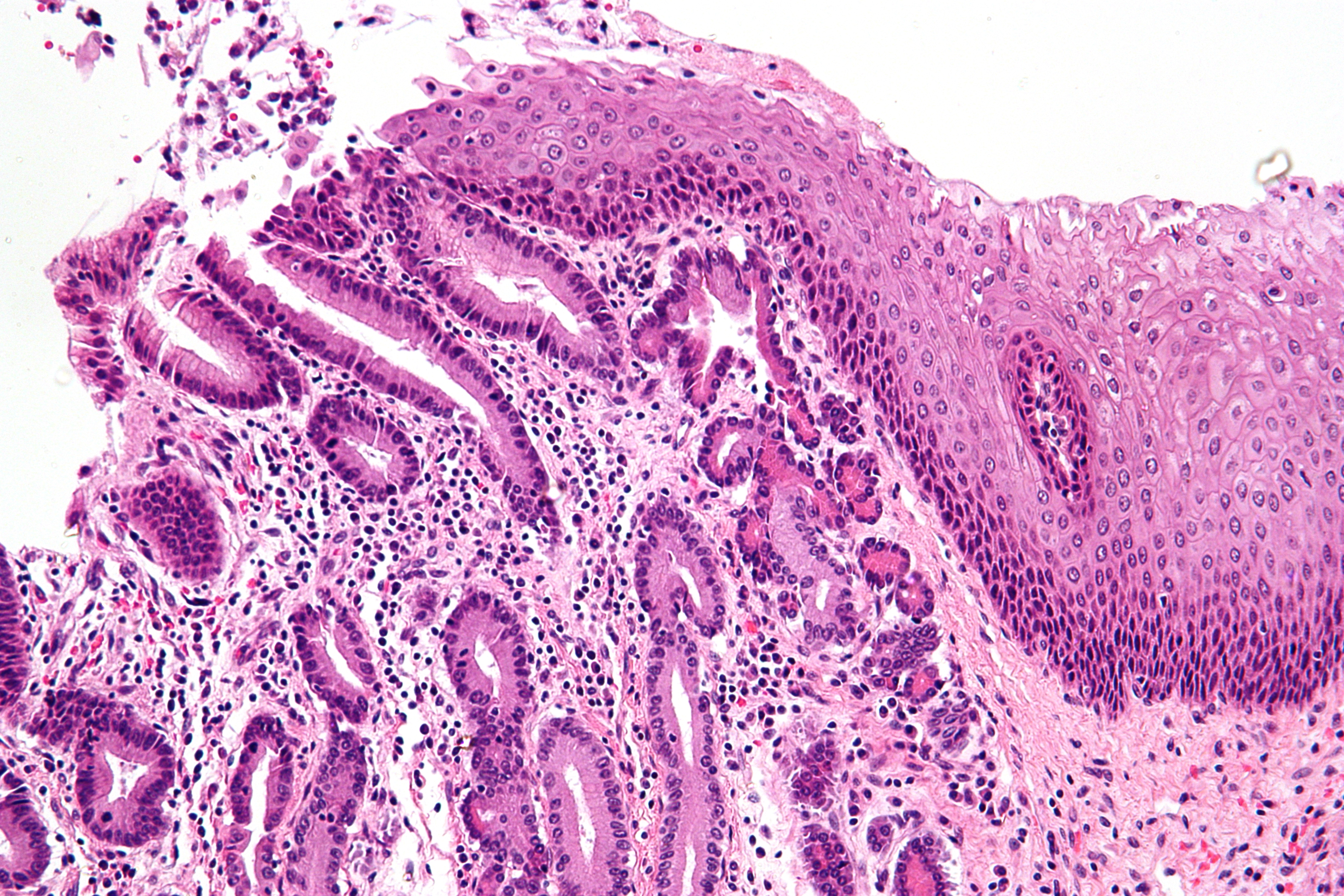

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which the esophagus, the muscular tube that carries food and saliva from the mouth to the stomach, changes so that some of its lining is replaced by a type of tissue similar to that normally found in the intestine. This process is called intestinal metaplasia.

While Barrett's esophagus may cause no symptoms itself, a small number of people with this condition develop a relatively rare but often deadly type of cancer of the esophagus called esophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett’s esophagus is estimated to affect about 700,000 adults in the United States. It is associated with the very common condition gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD.

Normal function of the esophagus

The esophagus seems to have only one important function in the body—to carry food, liquids, and saliva from the mouth to tire stomach. The stomach then acts as a container to start digestion and pump food and liquids into the intestines in a con- trolled process. Food can then be properly digested over time, and nutrients can be absorbed by the intestines.

The esophagus transports food to the stomach by coordinated contractions of its muscular lining. This process is automatic and people are usually not aware of it. Many people have felt their esophagus when they swallow something too large, try to eat too quickly, or drink very hot or very cold liquids. They then feel the movement of the food or drink down the esophagus into the stomach, which may be an uncomfortable sensation.

The muscular layers of the esophagus are normally pinched together at both the upper and lower ends by muscles called sphincters. When a person swallows, the sphincters relax automatically to allow food or drink to pass from the mouth and into the stomach. The muscles then close rapidly to prevent the swallowed food or drink from leaking out of the stomach back int0 the esophagus or into the mouth. These muscles make it possible to swallow while lying down or even upside-down. When people belch to release swallowed air or as from carbonated beverages, the sphincters relax and small amounts of food or drink may come back up briefly; this condition is called reflux. The esophagus quickly squeezes the material back into the stomach, and this is considered normal.

While these functions of the esophagus are obviously an important part of everyday life, people who must have their esophagus removed, for example because of cancer, can live a relatively healthy life without it.

GERD

Having liquids or gas occasionally reflux is considered normal. When it happens frequently, particularly when not trying to belch, and causes other symptoms, then it is considered a medical problem or disease. However, it is not necessarily a serious one or one that requires seeing a hysician.

The stomach produces acid and enzymes to digest food, and when this mixture refluxes into the esophagus more frequently than normal or for a longer period o1 time than normal, it may produce symptoms. These symptoms, often called acid reoux, are usually described by people as heartburn, indigestion, or “gas.” The symptoms typically consist of a burning sensation below and behind the lower part of the breastbone or sternum.

Almost everyone has experienced these symptoms at least once, typically as a result of overeating. Other things that provoke GERD symptoms include being overweight, eating certain types of foods, or being pregnant. In most people, GERD symptoms may last only a short time and require no treatment at all. More persistent symptoms are ohen quickly relieved by over-the-counter acid-reducing agents such as antacids. Common antacids are

- Alka-Seltzer

- Maalox

- Mylanta

- Pepto-Bismol

- Riopan

- Rolaids

- Other drugs used to relieve GERD symp- toms are antisecretory drugs such as hista- mines (H¿) blockers or proton pump inhibitors. Common H2 blockers are

- cimetidine (Tagamet HB)

- famotidine (Pepcid AC)

- nizatidine (Axid AR)

- ranitidine (Zantac 75)

- Common proton pump inhibitors are

- esonieprazole (Nexium)

- lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- omeprazole (Prilosec)

- pantoprazole (Protonix)

- rabeprazole (Aciphex)

People who have symptoms frequently should consult a physician. Other diseases can have similar symptoms, and prescription medications in combination with other measures might be needed to reduce reflux. GERD that is untreated over a long period can lead to complications, such as an ulcer in the esophagus that could cause bleeding. Another common complication is scar tis- sue that blocks the movement of swallowed food and drink through the esophagus; this condition is called stricture.

Esophageal reflux may also cause certain less common symptoms, such as hoarseness or chronic cough, and sometimes provokes conditions such as asthma. While most patients find that lifestyle modifications and acid-blocking drugs relieve their symp- toms, doctors occasionally recommend surgery. Overall, GERD is one of the most common medical conditions. Some 20 percent of the population can be affected over a lifetime.

GERD and Barrett’s esophagus

The exact causes of Barrett’s esophagus are not known, but it is thought to be caused in part by the same factors that cause GERD. Although people who do not have heartburn can have Barrett’s esophagus, it is found about three to five times more often in people with this condition.

Barrett’s esophagus is uncommon in children. The average age at diagnosis is 60, but it is usually difficult to determine when the problem started. It is about Wice as common in men as in women and much more common in white men than in men of other races.

Barrett’s esophagus and cancer of the esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus does not cause symptoms itself and is important only because it seems to precede the development of a particular kind of cancer-esophageal adenocarcinoma. The risk of developing adenocarcinoma is 30 to 125 times higher in people who have Barrett’s esophagus than in people who do not. This type of cancer is increasing rapidly in white men. The increase is possibly related to the rise in obesity and GERD.

For people who have Barrett’s esophagus, the risk of getting cancer of the esophagus 15 Small: less than 1 percent (0.4 percent to 0.5 percent) per year. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is often not curable, partly because the disease is frequently discovered at a late stage and because treatments are not edective.

Diagnosis and screening

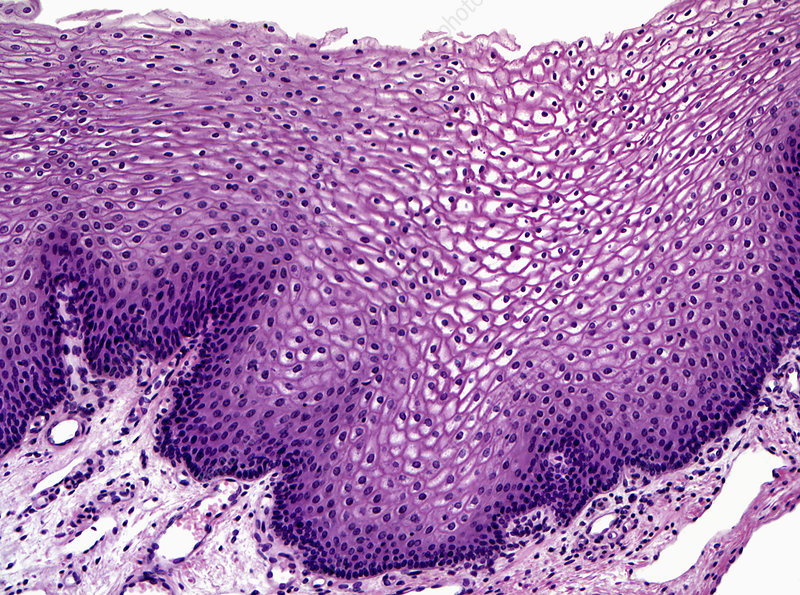

Diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus is not easy. At the present time, it cannot be diagnosed on the basis of symptoms, physical exam, or blood tests. The only useful test is upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy. In this procedure, a flexible tube called an endoscope, which has a light and miniature camera, is passed into the esophagus. If the tissue appears suspicious, then biopsies must be done. A biopsy is the removal of a small piece of tissue using a pincher-like device passed through the endoscope. A pathologist examines the tissue under a microscope to confirm the diagnosis.

Looking for a medical problem in people who do not know whether they have one is called screening. Currently, there are no commonly accepted guidelines on who should have endoscopy to check for Barrett's esophagus. Among the many reasons for the lack of firm recommendations about screening are the great expense and occasional risk of side effects of the test. Also, the rate of finding Barrett’s esophagus is low, and finding the problem early has not been proven to prevent deaths from cancer.

Many physicians recommend that adult patients who are over the age of 40 and have had GERD Symptoms for a number of years have endoscopy to see whether they have Barrett’s esophagus. Screening for this condition in people who have no symptoms is not recommended.

Treatment

Barrett’s esophagus has no cure, short of surgical removal of the esophagus, which is a serious operation. Surgery is recommended only for people who have a high risk of developing cancer or who already have it. Most physicians recommend treat- ing GERD with acid-blocking drugs, since this is sometimes associated with improvement in the extent of the Barrett’s tissue. However, this approach has not been proven to reduce the risk of cancer. Treating reflux with a surgical procedure for GERD also does not seem to cure Barrett’s esophagus.

Several different experimental approaches are under study. One attempts to see whether destroying the Barrett’s tissue by heat or other means through an endoscope can eliminate the condition. This approach, however, has potential risks and unknown effectiveness.

Surveillance for dysplasia and cancer

Periodic endoscopic examinations to look for early warning signs of cancer are generally recommended for people who have Barrett’s esophagus. This approach is called surveillance. When people who have Barrett’s esophagus develop cancer, the process seems to go through an intermediate stage in which cancer cells appear in the Barrett’s tissue. This condition is called dysplasia and can be seen only in biopsies with a microscope. The process is patchy and cannot be seen directly through the endoscope, so multiple biopsies must be taken. Even then, it can be missed.

The process of change from Barrett’s to cancer seems to happen only in a few patients, less than 1 percent per year, and over a relatively long perlod of time. Most physicians recommend that patients with Barrett’s esophagus undergo periodic surveillance endoscopy to have biopsies. The recommended interval between endoscopies varies depending on specific circumstances, and the ideal interval has not been determined.

Treatment for dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma

If a person with Barrett’s esophagus is found to have dysplasia or cancer, the doctor will usually recommend surgery if the person is strong enough and has a good chance of being cured. The type of surgery may vary, but it usually involves removing most of the esophagus and pulling the stomach up into the chest to attach it to what remains of the esophagus. Many patients with Barrett’s esophagus are elderly and have many other medical problems that make surgery unwise; in these patients, other approaches to treating dysplasia are being investigated.

Hope through research

- Many important questions about Barrett’s esophagus need further research to

- find better ways to identify people who have the problem

- find out what causes it

- test treatments that may prevent or eliminate it

- find better treatments for people who have Barrett’s esophagus with cancer

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the National Cancer Institute sponsor research programs to investigate Barrett’s esophagus.

Points to remember

- Many important questions about Barrett’s esophagus need further research to

- In Barrett’s esophagus, the cells lining the esophagus change and become similar to the cells lining the intestine.

- Barrett’s esophagus is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD.

- A small number of people with Bar- rett’s esophagus may develop esophageal cancer.

- Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and biopsy.

- People who have Barrett’s esophagus should have periodic esophageal examinations.

- Taking acid-blocking drugs for GERD nay result in improvements in Bar- rett’s esophagus.

- Removal of the esophagus is recom- mended only for people who have a high risk of developing cancer or who already have it.

Additional resources

For more information about GERD or Barrett’s esophagus, contact

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD), Inc.

P.O. Box 170864

Milwaukee, WI 53217

Phone: 1-888—964-2001 or (414) 964-1799

Fax: (414) 964—7176

Email: idgd@iffgd.org

Internet: www.iffgd.org

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

National Institutes of Health 31 Center Drive

Building 31, Room 10A—19

Bethesda, MD 20892

Phone: (301) 496-6641

Fax: (301) 49W846

Internet: www.nci.nih.gov

The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. Trade, proprietary, or company names appearing in this document are used only because they are considered necessary in the context of the information provided. If a product is not mentioned, this does not mean or imply that the product is unsatisfactory.

National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

2 Information Way

Bethesda, MD 20892—3570

Phone: 1—80W91—5389 or (301) 654-3810

Fax: (301) 907—8906

Email: nddic@info.niddk.nih.gov

The National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse (NDDIC) is a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). The NIDDK is part of the National Institutes of Health under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Established in 1980, the clearinghouse provides information about digestive diseases to people with digestive disorders and to their families, health care professionals, and the public. NDDIC answers inquiries, develops and distributes publications, ind works closely with professional and patient organizations and Government agencies to coordinate resources about digestive diseases.

Publications produced by the clearinghouse are carefully reviewed by both NIDDK scientists and outside experts. This fact sheet was reviewed by G. Richard Locke, M.D., Mayo Ginic; and Joel Richter, M.D., Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

This publication is not copyrighted. The clearinghouse encourages users of this tact sheet to duplicate and distribute as many copies as desired. This fact sheet is also available at www.niddk.nih.gov under “Health Information”.

share now!

go n' tweet it!

let's pin this!

download this!